You probably didn’t watch the NCAA Division I men’s soccer championship game between Vermont and Marshall on Monday night. (I did!) It went to overtime — where this happened:

Pretty exciting, right? I mean, it’s the first non-skiing national championship in the history of the University of Vermont! What a story! This is what college soccer — and college sports — is all about!

Except, well, not really. Dig even slightly below the surface and you see that college soccer is, in fact, changed drastically over the past four years — and in ways that are deeply damaging to its future prospects and of the continued growth of the sport in this country.

Let me explain.

I am going to be broadening out the content offering of “So What” over the next year — branching more into sports, music and culture. I will still be MAINLY writing about politics, of course. I need your support to continue doing this work full-time. You can become a paid subscriber for $6 a month or $60 a year.

It may seem odd to you, if you don’t follow college soccer, that the national championship was between Marshall (a school in West Virginia) and Vermont. When you think of college sports/soccer powerhouses, you wouldn’t first think of schools in Vermont or West Virginia.

How did Marshall and Vermont get good? They brought in international players. Lots of them.

Of the 22 starters on the field in Cary, North Carolina in the national championship game Monday night, 16 of them were internationals. That’s almost 75%!

Here’s the breakdown:

Vermont (6 internationals, 5 Americans)

Goalkeeper: Germany

Defender: PA

Defender: NJ

Defender: Canada

Midfielder: Gibraltar

Midfielder: Germany

Forward: Israel

Forward: Germany

Forward: Maine

Forward: PA

Marshall (10 internationals, 1 American)

Goalkeeper: Serbia

Defender: England

Defender: Japan

Midfielder: Brazil

Midfielder: France

Midfielder: Japan

Midfielder: PA

Midfielder: Denmark

Forward: Germany

Forward: Brazil

Forward: Japan

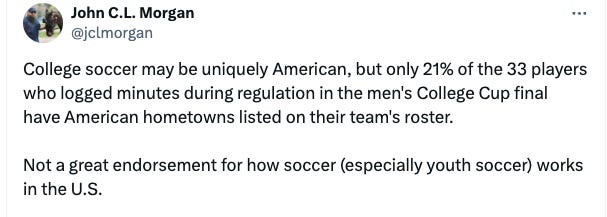

And it’s not just the starters. It’s (almost) everyone who saw the field during the game. This stat is eye-popping:

As is this: All three goal scorers in the championship game were foreign-born; two are Germans, one is Hungarian.

And here’s one more stat for you: Of the 28 players on the Marshall roster, 3 were born in the United States. Three!

How did we get here?

Marshall started the trend back in 2020 when, with a roster chock full of foreign-born players, they won the school’s first-ever men’s soccer national championship.

If that success seemed to come out of nowhere, well, that’s because it did. Marshall had never WON an NCAA tournament game before 2019. Not one! In fact, here’s the team’s record in the two previous seasons: 8-10-1 (2017), 8-9-3 (2018).

What changed? I mean Marshall’s coach today is the same guy who was the coach in 2017. Did he suddenly get much better at his job? Or did he realize he could load his roster with internationals and sprint to the top of the sport?

Uh, yeah.

Look. I understand why this is happening.

From the athlete’s perspective, it’s a great deal. Most of these guys played for elite academies across Europe. At some point in their teen years, it became clear that they weren’t first-team selections and wouldn’t likely play professionally for that club.

And so, America looks very appealing! A free college education. In the hub of the modern world. And you are likely to be able to play professional soccer — in the U.S. or elsewhere around the world — when you are done with school.

It’s a pretty great deal! And I don’t begrudge the international players who leap at it in ANY WAY.

And from the coaching perspective, the only real imperative — especially at an elite program — is to win. Yes, we talk the talk about student athletes and the college experience and all that but anyone who knows big-time college athletics — basketball and football especially — knows that winning is all that fans and donors care about. And if the coach wins, the coach will not only keep his or her job but will get more money to do it.

It’s a pretty simple equation. If more international players help you win, and winning is all that matters, you stock your roster with international players.

Marshall is FAR from alone in this. While they lead the way back in 2020, other schools have rushed to copy their international-heavy approach.

The team Marshall beat in the national semifinals — Ohio State — started 7 internationals. Denver, who lost to Vermont in the other semifinal, is the exception to the rule — with only 2 internationals among its starting 11.

(Sidebar: Georgetown, my alma mater, is another exception. The Hoyas have only 2 international players on the roster — and only 1 is a starter.)

The number of international players on college rosters is accelerating rapidly. And the successes of both Marshall and Vermont affirm that a starting 11 laden with internationals is the best path to quick turnarounds and success at the elite level.

Why is this a problem?

Simple. Because if we want to grow soccer in this country, we are never going to do it by importing the very-good-but-not-elite players from other countries!

Truly elite — like national team level — American players will still succeed under this system (or, really, any system). Most of those players — like 14-year old phenom Cavan Sullivan — will go to big clubs in Europe to make their living.

But, for the American players who are very good but not at that ultra-elite level, the number of opportunities for them to continue to play the sport at the highest collegiate level is shrinking. The rosters are taken up by more and more internationals. And, in some cases major programs aren’t even recruiting American kids anymore!

One anecdote to prove the point: Last week in Indio, California was the MLS Next Fest — one of the premier recruiting events for soccer in the country. This showcase features the top high school age talent from across the country. And yet, a major college program — in a BIG conference — sent NONE of their people to the event. Why not? They were abroad — scouting international players.

This all has a trickle-down effect. If there are less Division I spots available for the outstanding American players, those players are pushed down to Division II and Division III schools. And they wind up taking slots from kids who, a decade ago, would have had successful four-year careers at those lower-division schools.

Then there’s the recent settlement by the NCAA that will limit the roster sizes of most Division I programs. The average Division I men’s soccer roster this season was 32.5. Starting next year, schools will be limited to 28 roster slots.

Add it all up and you get this: Less and less American kids will have the opportunity to play college soccer. Which means less American kids in the soccer system. Less chances to produce great pro players, yes, but also to grow the game in this country from the top travel programs on down.

“It truly is the most difficult time to be a high end American soccer player to find a home that I can think of,” Brian Wiese, the head soccer coach at Georgetown, told me on Tuesday.

To be clear: I am not a neutral party in this. I have a teenage son who wants to play college soccer. I want him to be able to realize that dream. And the more international players seed college rosters, the harder it becomes for someone like him.

But, my own personal biases aside, I do think that this is a MAJOR problem for the sport. And it is something the NCAA — if it ever decided to act — MUST do something about.

What? How about a limit on the number of internationals on the roster? Like, say, 6? That would still allow foreign-born players to come to the U.S. and experience college soccer without boxing out American kids entirely.

That’s one idea. And I don’t claim to have a monopoly on good ones. But, the system as it is currently comprised is NOT working. And without change at the NCAA level, college soccer will cease to exist as a dream for lots and lots of American kids.

And that is a damn shame.

I too am a college soccer fan -- go Zips! And congrats to the Catamounts for a great Cinderella run, first unseeded team (top 16 of 48 are seeded) to win it all since the UCSB Gauchos in 2006. (Caveat: the Marshall Thundering Herd was unseeded when they won the covid-reduced 2020 championship, in which the top 8 of 32 teams were seeded.) And gotta love all those weird team names!

My take: this is just a microcosm of the big issue of global competition. Chris wants protectionism for US "workers". But at many universities now, rich foreign students paying full tuition is what pays the bills. So hard to say they can't also play on their college's teams.

Another issue is the US-specific conflation of semi-pro sports and education. I'd like to see these separated, as they are in the rest of the world, though the chances of that happening are zero.

What you saw last night -- and I watched at least a dozen games of the college cup including the championship game -- is a symptom of a larger problem in US MEN's soccer. The fundamental problem with US MEN's soccer -- which I believe you have addressed here -- is its pay-to-play model that isn't producing players good enough to play at the college level here. The MEN's clubs in the US aren't interested in developing the talent; they're primarily interested in growing their programs and chasing the dollars. Until we address that, we are going to continue to spin our wheels and look for short-term fixes such as limiting the cap on the number of international players on a roster. P.S. the Women's college cup also is loaded with international players and I would argue that the women's game at the high school and college levels is far superior than the men's. But that's a topic for another day!!